Prelude to Assaye II : An Assessment of the Maratha Power

On the 23rd of September, 1803, an army of Daulat Rao Scindia, Maharaja of Gwalior fought an EIC army, led by Major-General Arthur Wellesley, here we analyze the Maratha power leading up to Assaye

We finally return to Assaye.

This is my 2nd post on the subject, with more to come. First post is here.

The post serves two purposes.

The first, being the much awaited volume in a year long series anticipation.

The second, is in my opinion, much more important.

This post serves as a platform for me to reassess any previous notions I had about this chapter of history, to look at the issue from a Maratha perspective and provide a more in depth analysis for the Maratha forces using primary sources.

Let us set the stage again.

We left the future Duke of Wellington, at the critical juncture of his Deccan Campaign of the Second Anglo-Maratha War, just before the commencement of the sanguinary encounter with the Maratha forces of Daulat Rao Scindia at Assaye, 1803.

Let us leave the Iron Duke there, and trace our steps backwards, much earlier, to the year 1790.

A Tumultuous Decade (1790-1800) : The Political Background of the Second Anglo-Maratha War

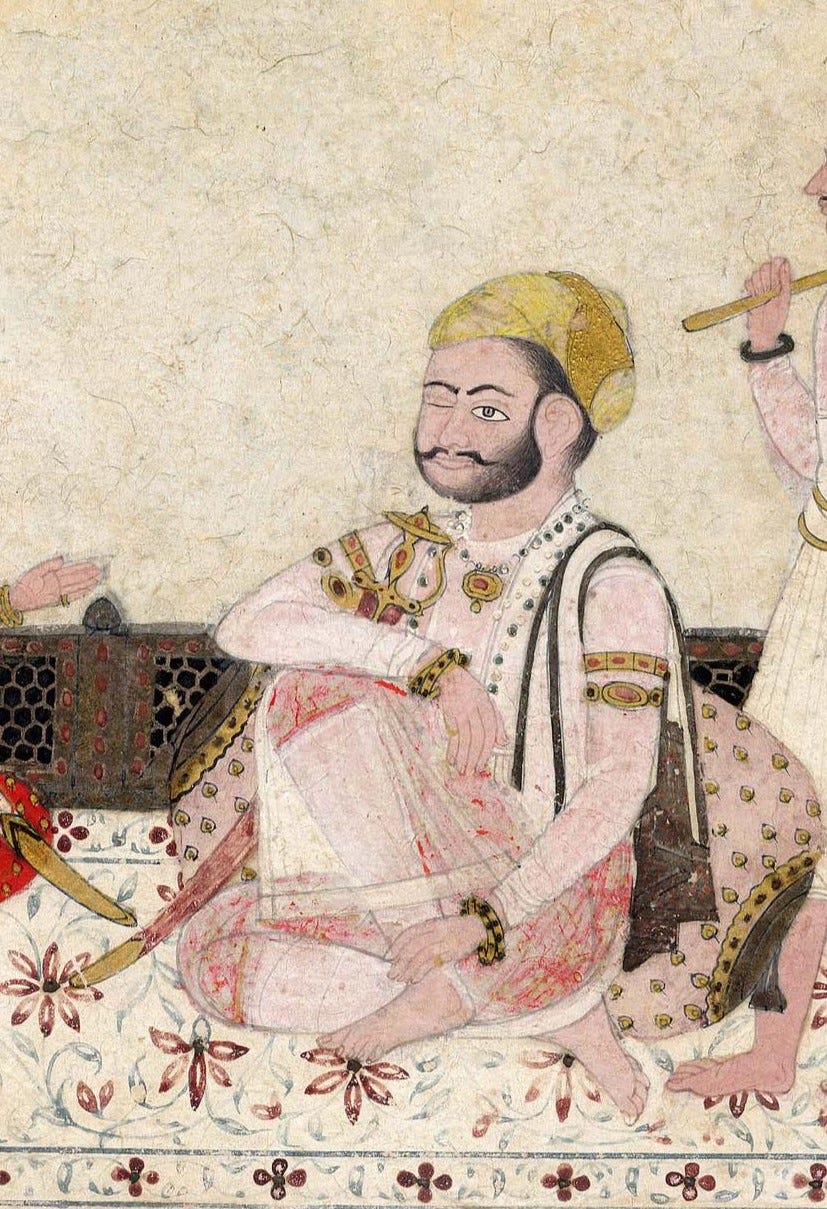

Around the year 1800, the Maratha power was no longer the kingdom it was under Shivaji ; a nation at arms guided by a singular will, nor were they the same gathering of Sardars united under the will, ambition and competence of the Peshwas. Chhatrapati Shahu was dead and the successors of the Peshwas lived unfortunately short lives.

Maratha Sardars, who had ventured to rich Gujarat and Malwa, settled there in personal bases of power, and involved themselves in northern intrigue, the politics of Delhi and the Rajputana.

A new era thus began, of virtually independent action by the chiefs, which led to friction among the more powerful ones, namely the two who capture popular imagination more than the rest, the Holkars and the Scindias, and who are without a doubt the Maratha protagonists of the 2nd Anglo-Maratha War.

Competition between the two houses had been present since the beginning, by the late 1780s, their rivalry approached its zenith, both vying for supremacy at Delhi and Rajputana.

Inevitably, ambition led to open conflict, in the beginning of 1791.

The two Maratha houses bled the Maratha power from within, with the Holkars being bested by the Scindias by 1793.

By the late 1790s, Yashwantrao Holkar gained his patrimony, & assembled a formidable army.

Soon, the Holkar bled Scindia in retaliation, & on top of this, Daulat Rao was besieged by factional politics and civil war at home.

The "Bais", the wives of the deceased Mahadji Scindia, uncle of Daulat Rao, had themselves engaged in intrigue with sympathetic parties at the Gwalior court & had embroiled the Scindia house in an unnecessary and bloody civil war.

All this, between 1797-1803, immediately before the 2nd Anglo-Maratha War.

Indeed, the final episode of this decade long prelude to Assaye and the War, played out in early 1802 itself, with Yashwantrao Holkar's march on Poona, which as we discussed in my previous post, forced the Peshwa to seek British aid and once again involved the Company in Maratha politics.

Without examining in excruciating detail the immediate causes & the many varied context of the war, we must understand the following :

Imperial justifications for the war would have us believe in the just cause of the Governor-General Richard Wellesley, in restoring the Peshwa to his seat at Poona, as per the terms of the treaty of Bassein, signed December 31st, 1802.

However, this pattern of political opportunism, used to exploit political weakness in native states in order to sign favourable treaties and use the pretext of restoration and protection to justify overlordship & control, was nothing new, infact, Wellesley's predecessor, Hastings, had paid a costly & tiring price for his meddling in native affairs for bureaucratic gain & expansionism.

The involvement of the EIC in the Maratha affairs was the effect of a policy of expansion pursued by Richard Wellesley.

Maratha sardars on the other hand, were divided.

There were three principal powers among the Marathas, who if they so wished, could have with coordinated action performed a repeat of the First Anglo-Maratha War.

The Maharaja of Gwalior, Daulat Rao Scindia.

The Maharaja of Nagpur, Raghuji Bhonsle II.

And, last but certainly not the least, The Maharaja of Indore, Yashwantrao Holkar.

The 3 men, unfortunately for the Marathas, were not united by some grand cause.

The primary cause which pulled them into the war was their refusal to accept the terms of the Treaty of Bassein, but this alone did not mobilize them into coalescing their agencies.

Indeed, Holkar sat out the 1803 campaigns, and began his war in earnest in 1804.

Daulat Rao was on the other hand, not fortunate enough to “sit this one out” even for a moment.

In secret, the "offensive" of Richard Wellesley, from his H.Q in Bengal, via the ordnance of capital, intrigue & espionage had already begun to dull Scindia's military edge since 1801-2, for Wellesley had announced that any officer whose home country was Britain, who would be found commanding and aiding the armies of Scindia, would be considered a traitor.

Such was the effect of this “Proclamation” that between 1802-Sepetember, 1803, European officers, including Perron himself, were busy finding safe passage into Company protection &/or service.

For example, the only commander of note at the battle of Assaye, being Pohlmann, had accepted the Governor-General, Richard Wellesley’s Proclaimation, on the 12th of September, a mere 11 days before the battle.

It would also be Scindia whose forts, lands & armies the British would ultimately destroy first and foremost in Hindustan & the Deccan, when the Bengal & Madras armies marched in the field in 1803.

These were the realities that confronted the Maratha chiefs, and for our interest, Daulat Rao Scindia in particular, in 1803, before the encounter of Assaye.

A Numbers Game? : Analysis of Scindia's Army at Assaye from British sources

To get a sense of the scale of the Battle of Assaye we first need to establish numbers for both sides.

This post is dedicated to the Maratha forces.

At Assaye, Wellesley faced primarily, the forces of Daulat Rao Scindia.

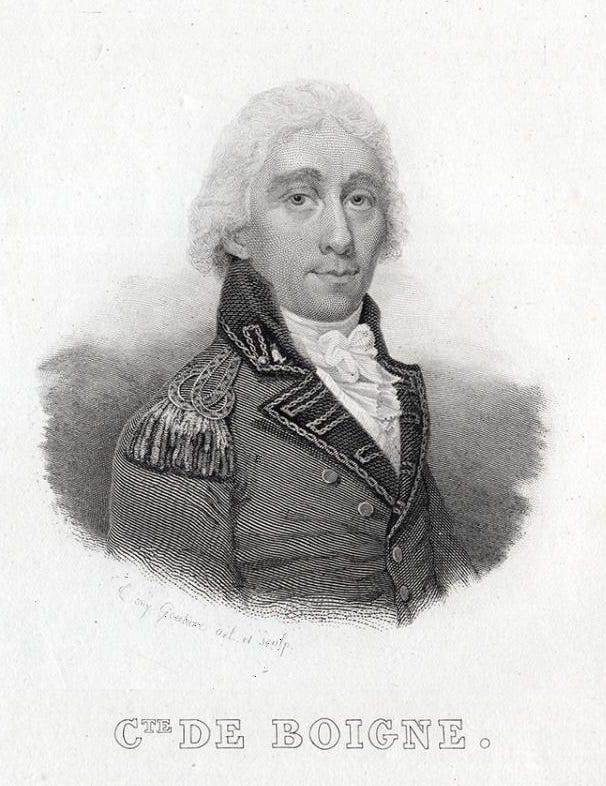

The most lethal component of the army of Daulat Rao Scindia were his "regular corps", known as “Campoos”, named as such by the Savoyard military adventurer, Benoit De Boigne, who raised these corps in 1784, for the predecessor of Daulat Rao, his uncle, the great Mahadji Scindia.

It will be this force in particular that will absorb the full attention of this post, the cavalry not being our concern here.

Utilizing the best available military labour in North India, recruiting from a variety of ethnicities, the corps was the pinnacle of military organizational and technological sophistication, reached by any regular corps in India, in the 18th century.

The corps was officered by a sprinkling of higher level European mercenaries, from company to brigade levels, working alongside a native officer corps & native NCOs.

Needless to say, the corps owed its success to its organizational efficiency, the discipline and physical courage of its native soldiers coupled with the personal courage, training & competence of its European & native officer corps.

As a point of comparison, with the exception of the volume and concentration of the officer corps at unit levels, the Campoos were interchangeable with EIC infantry formations in terms of their effectiveness.

Now let's talk numbers.

Thanks to a letter written to the Court of Directors, dated 5th February, 1794, from Poona, by a C.W Malet, we know what these formations looked like around 9 years before the war started.

Campoos were organized into Brigades.

De Boigne's 1st and 2nd Brigade were raised by 1790.

The 3rd was raised in 1793.

Each Brigade had 10 battalions.

A battlalion had 8 companies.

528 Combatants to a Battalion, plus staff made it 538 men to take the field/battlalion

5,380 men/Brigade plus a Brigade Major and a C.O for a Brigade, so 5,382 privates + officers, colour bearers, drummers & fifers.

To each Brigade, were 200 horse & a 1,000 man Rohilla corps.

This brings the total to around 6,382 infantry/brigade, on paper, or 6,400 for convenience.

Brigades were divided into 6 musket & 4 matchlock battalions.

Each battalion was issued 2 3pdrs. and 2 6pdrs. respectively & each flintlock battlalion was issued a Howitzer, to compensate for lesser firepower compared to matchlocks.

So, 46 guns/brigade.

But we cannot simply rely on 1794 numbers to determine the strength of Scindia's army in 1803.

In December, 1795, De Boigne handed an honourable resignation to Scindia.

In September of that year, Perron had assumed command of the regular corps of Scindia.

From 1798-1802, these forces were embroiled in bloody & incessant conflicts.

The disturbance with the Bais and Lakhwa Dada, the battles of Jaipur, Seondha, Ujjain, Indore and Poona, all had destructive consequences for the officer corps & unit strength of the Campoos.

Perron had raised a 4th Brigade in 1801 & a 5th in 1803.

On paper, each of the 5 brigades in 1803 should have had a total strength of 6,400 infantry (10 battalions each + Rohillas), along with a complement of 200 cavalry & non-combatants & artillerymen for 20 3pdrs., 20 6pdrs., and 6 howitzers, per brigade.

However, the wars with Yashwantrao Holkar had mauled these formations, and they had undergone changes.

In 1801, Holkar had defeated around Ujjain, 6 battalions of Scindia & taken around 30 cannons.

2 under Captain McIntyre, 4 under George Hessing, with 3/5ths of the latter completely killed, 1/5th wounded.

In late 1802, around Poona, Holkar had destroyed another 4 battalions under Captain Dawes.

The 4th & 5th Brigades of Perron raised in 1801 & 1803 were fresh, raw recruits.

According to L.F Smith, a veteran of Scindias regular corps, there were 416 sepoys/battalion, 530 men including officers, drummers & fifers, with ~150 men in the artillery to man the battalion guns, another 29 men in staff. Total 709 men in a battalion.

Every compleat, brigade, had three battering guns, ten howitz, two mortars, and thirty-fix field pieces, and four thouſand muſkets ; two hundred regular horſes and acorps of five hundred Rohillas, for irregular fervice.

These are different considerations than before.

Taking away 200 regular horse & 500 Rohilla skirmishers from 6000, gives us an even 5,300 men.

Considering that “a brigade had 4,000 muskets”, we can further conclude that these forces were not 10 battalion strong, but probably around 6-8, the remaining being staff, artillery personnel etc.

The distribution of officers remains roughly the same.

Matchlock battalions are not mentioned separately, though the howitzer seems to now be issued to all battalions, seemingly compensating for the loss of firepower accrued by replacing all matchlock battalions with flintlocks.

So, by 1803, the numbers of Scindia's battalions/brigade were diminished, as well as the number of sepoys/battalion.

At Assaye, Scindia had with him :

Colonel Pohlmann's Brigade : 6,000 men

Dupont's Brigade : 2,500 men

Sumroo's Brigade : 2000 men

Note :

Pohlmann's Brigade seems to be at full strength on paper, so 4000 of them were probably infantry. This would imply 7-8 battalions.

Dupont's Brigade were entirely fresh recruits, since he commanded the Filoze corps destroyed by Holkar earlier at Ujjain & Poona.

Traditional historiography surrounding the battle, drawing mostly from Imperial histories and British eye-witness accounts tend to take these numbers as factual when considering the Maratha forces at Assaye, placing the total at 10,500 infantry. As seen from the analysis above, this is obviously incorrect.

Furthermore, on the Sumroo Brigade, Cooper notes :

The Begum had led Sindia to believe she would support him but she carefully kept manoeuvring her battalions to keep them out of combat at places like Assaye. Later, when British appeals to her brigade commander Saleur fell on deaf ears, she wrote to him in French and addressed a separate 'Persian Hookumnama' to her sepoys indicating the deal was done and it was time to enter British service....Begum Sumru had ordered four battalions, totalling some 2,000 men, to march from the Deccan to Rajasthan in order that they might 'go over' to General Lake. - pg. 269-270

This is confirmed by Major-General Wellesley himself, in his despatches :

The only brigade that escaped on the 23rd was part of Begum Sumroo's. They were with the baggage, and got off in safety

But this is not all, Wellesley also says :

four battalions of Dupont. The latter was formerly Filosé's, and was entirely destroyed by Holkar, in the action at Ougein.

So, in the weeks after the battle, Wellesley admitted that not only, did he not face the entire force that was assembled in the Deccan under Scindia, but also, that this force was not the same titan as it was under De Boigne.

Yet, imperial historiography & even popular imagination places the Maratha numbers grossly high.

The only functional force, was that of Pohlmann.

But as discussed above, he resigned from Scindia's service for Company protection, along with Grant and MacCulough.

So, the only competent and willing force had lost its competent and willing commanders.

With a thinning of the officer corps, came loss of tactical edge.

Plus, as Wellesley notes :

According to Sydenham's, and this account, these are the only two brigades that have not been engaged, and are not destroyed; excepting, possibly, one or two battalions of Begum Sumroo's, and one of Pohlmann's which were sent off with the baggage at the commencement of the battle of Assye.

Yet, while Wellesley admits these discrepancies, imperial histories like Thorn's & memoirs like that of Blakiston continue to serve as primary source materials for Assaye, quoting a 10,500 strong number for the Campoos of Scindia & naming Pohlmann as the commander.

The above evidence also suggests that a clear consensus in British sources is lacking when it comes to how many battalions were actually engaged at Assaye.

“Many Times Our Number” : Analysis of a contemporary Marathi source for Assaye

We may now turn to Marathi sources.

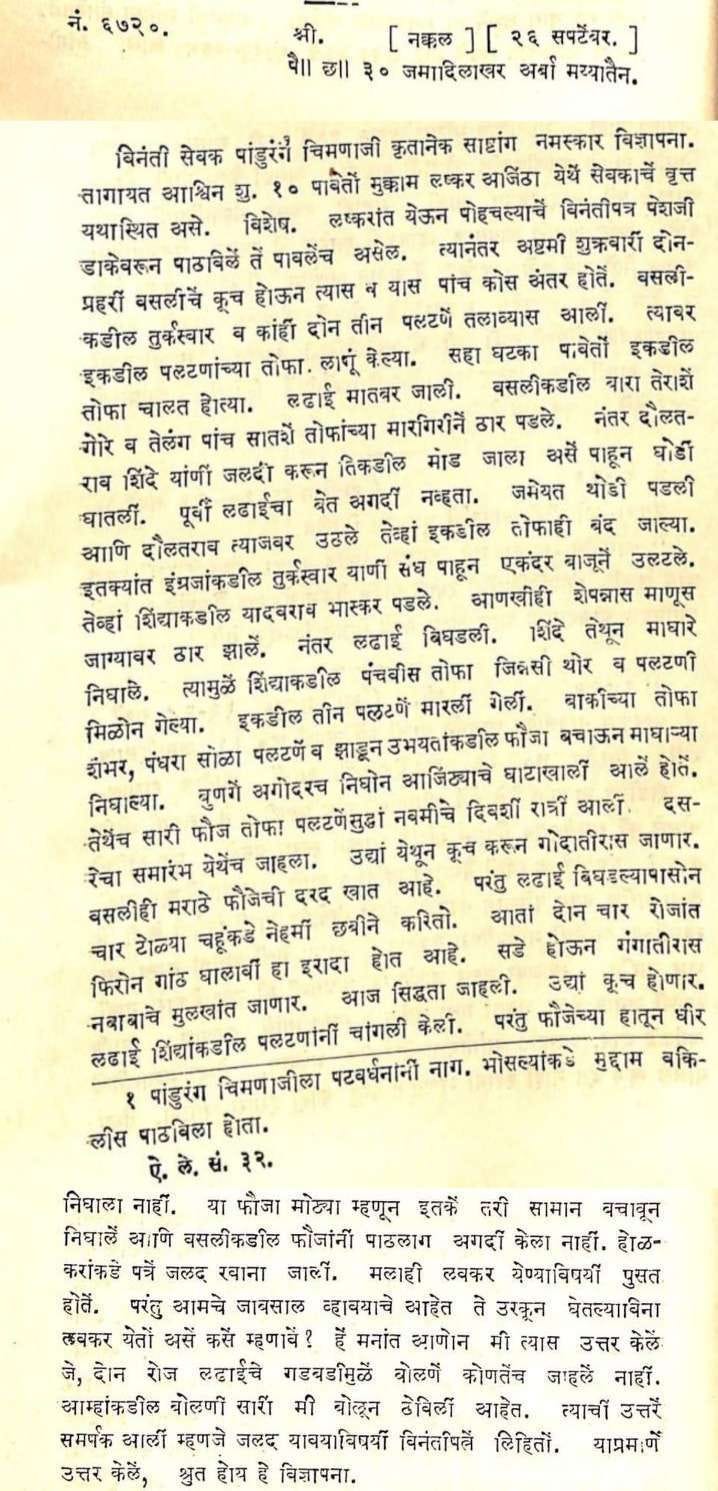

At the minimum, at Assaye, Scindia was able to potentially field 18-19 "battalions" or as they are called in Marathi records, paltans, based on a letter sent by Pandurang Chimmaji, on the 26th of September, 1803, three days after the fateful battle.

Here's a translation of the letter, for better understanding :

26 September, 1803

Humble servant Pandurang Chimaji offers countless prostrations and respectfully submits this report.

...On the 8th day (Shukla Paksha), Friday, at midday, the Basali (Wellesley) contingent moved, and they were about 5 kos (9.5miles) away. Turk cavalry from Wellesley and two or three infantry units arrived near the lake. Our artillery fired upon them. Our cannons continued firing for more than 2 hours. A fierce battle ensued. Around 1,300 European and 500-700 Telang soldiers from Wellesley were killed by cannon fire.

Later, Daulatrao Shinde, seeing the enemy lines breaking, quickly ordered a cavalry charge. Initially, there was no plan for battle. The forces were few, and when Daulatrao advanced, our cannons also ceased fire. At that moment, the Turk cavalry from the English side seized the opportunity and launched a counterattack. Yadhavrao Bhaskar from Shinde's side fell, and about 75 more men were killed on the spot. The battle then turned against us. Shinde retreated from there, resulting in the loss of 25 cannons, along with significant supplies and infantry. 3 of our infantry units were killed. The remaining 100 cannons, 15 or 16 infantry units, and the rest of the forces managed to retreat safely. The baggage train had already moved ahead and reached the base of the Ajintha ghat. The entire force, along with the cannons and infantry, arrived there on the night of the 9th.

The infantry under Shinde fought well, but the army lost its courage. Despite being a large force, they managed to save some equipment and retreat. The Wellesley forces did not pursue us aggressively...This is my respectful report.

---

The numbers from Pandurang start to make sense once we put them in context of all the British evidence discussed above, as well as a table of forces at the disposal of Scindia provided by Smith.

Pandurang's letter technically puts the total number of battalions present with Scindia at 18-19.

He mentions 3 "units killed" & the remaining "15-16 units" retreated.

We may be generous enough to assume he means 3 of the 15-16 killed, since we have no indication of there being 18-19 battalions at Assaye.

We know Pohlmann's Brigade was at full strength, probably 7-8 battalions. Sombre had 4, Dupont, as per reports had 4 too.

We also know that 3 battalions are confirmed by Pandurang's letter, to have been destroyed.

Wellesley was not aware of the escape of Sumroo's Brigade before the battle. It is therefore, unwise to trust in his assessment that a mere 1 battalion of Pohlmann's brigade left with the baggage.

With all the evidence thus far presented, we have the following numbers :

Of the 10,500 men, on paper that fought at Assaye, 2,000 of the Sumroo Corps, were never there.

Of the remaining 8,500, we know that 4,000 were infantry of Pohlmann's complete brigade.

Of the remaining 4,500 men, ~1200 men were Pohlmann's artillery personnel.

Of the remaining 3,300 men, ~700 were Pohlmann's Brigade cavalry & Rohilla corps.

We have a remaining 2,600, adjusting for a ~100 or so as staff for the Pohlmann Brigade, we have a 2,500 remainder to account for Dupont's Brigade, which was made up of 4 battalions.

Thus, on paper a total of 8,500 men were present with Scindia, of which at ~6000 were infantry (4000 of Pohlmann + 4 battalions of Dupont).

Wellesley further admits himself, that atleast one battalion of Pohlmann's, did not fight, but rather left with the baggage train.

This brings Scindia's total down to 7,790 men, & infantry numbers to around ~5,500 men.

We're not done yet!

We know from Wellesley's report, that of the 98 guns captured after the battle, 7 were brass howitzers, 22 were iron guns, 69 were brass guns.

Cooper suggests that out of 120 pieces present, 30-40 were not used.

Considering that the ordnance actually used must have been captured along with the one unused, we can say that of the 69 brass guns captured, a good number were not used.

A fraction of brass battalion guns usually 3 or 6 pdrs. were brought into action.

Pohlmann's complete brigade ought to have had 36 field pieces, 10 howitzers, 3 battering guns & 2 mortars.

Considering a battalion had ~147-150 men manning 4 field pieces & a howitzer, we can say that just to man the brigade field pieces & howitzers would take around 1200-1400 men.

The total number of men Wellesley confirms to have been killed, in his letter to his brother, the Governor-General, just 7 days after the battle, is also 1200.

So the total number of artillerymen has to be smaller, since the Company line did meet Maratha infantry.

Comparing Pandurang's number of 3 battalions killed (1500-1600 men) with Wellesley's suggested 7 battalions of Pohlmann (he admits atleast one escaped) plus 4 of Dupont, 11 battalions in all (5500 men), we can say that atleast both numbers account for the 1200 KIA figure quotes by Wellesley, plus an additional loss of infantry.

Another way to look at Pandurang's numbers, is to say, that 3 battalions, numbering 700-710, total 2,100-2,130 men in all (including artillery & staff) with their 12 field pieces were destroyed completely.

This number, both accounts for the 1200 killed in all, and around 12 brass pieces in action. Assuming even half the brass pieces were firing against the Company lines, this means another 5-6 battalions worth of artillery crews, or 750-900 men, bringing the total to 2,850-3,030 men.

We still can't account for 5,470-5,650 men, that Wellesley supposedly faced. But more on that in our next post.

For now, our assessment has arrived at a conclusion.

Making sense of it all

You have so far read a lot of numbers, evidences & calculations.

The point of this exercise is not to make a pedantic correction in popular history.

It is to address nearly 200 years of academic work on the subject which has assumed the numbers for the Marathas to have been far greater than that for the Company.

This ofcourse, would make sense when placed in the larger context of imperial perceptions of native martial prowess.

That a smaller force manned & officered by European could overcome several times its number.

But as we have seen, from our assessment of both British & Marathi sources, these are gross generalizations about a fairly complicated topic in history.

There were, by my estimation, no more than 2500-3000 men, at Assaye that actually gave battle to the Company army, of which the infantry component was around 1500, remaining being artillery men attached to their guns who died fighting by them.

A lot of confusion when reading imperial histories of the battle comes from the lack of disaggregation of Campoo battalion numbers.

The purpose of this post was to show with evidence that my estimation is accurate based on all the sources available.

In a future post, where we will discuss the actual battle itself we will see why these numbers provided above, make far more sense than the imaginative edicts of imperial historians & popular history.

These numbers are to serve as support to my analysis to come.

The following must be your takeaway from this article :

Scindia's force in September of 1803, was broken after his civil war & battles with Holkar.

A lot of his force was made up of fresh recruits.

His men lacked tactical leadership in the absence of officers who were running into the Company's arms to save their life thanks to Richard Wellesley's Proclamation.

The Scindia force at Assaye was around ~3000 strong, of which only around ~1500 were infantry, the rest being artillery crews.

The cavalry at Assaye, played a limited role, primarily strategic & a small engagement against the 74th, their numbers will be discussed in the next iteration of this series.

There is serious discrepancy between the number of men the Company army actually faced at Assaye & the ones present there on paper.

We will discuss the finer details of the last point made above in another part of this series in the future, but for now, I must end this chapter.

It has been an irregular posting schedule on my part, for that my readers have my deepest apologies, but I would rather take my time to breakdown historical myths & legends in detail, than give you a sub par product for the sake of a schedule.

If you've liked what you've read, and think I've made a worthwhile point here, kindly share the post with anyone interested in military history.

Until next time.

References :

Vasudev Khare, Aitihasik Lekh Sangraha, vol-XIV, no. 6720

Sir Jadunath Sarkar, Poona Residency Correspondence Volume 1 : Mahadji Scindia and North Indian Affairs 1785-1794, Bombay, 1986, no. 285

Major John Blakiston, Twelve Years' Military Adventure in Three Quarters of the Globe: Or Memoirs of an Officer who served in the Armies of His Majesty and of the East India Company between the years 1802 and 1814, in which are contained the Campaigns of the Duke of Wellington in India, and his last in Spain and the South of France, 2 vols., London, 1829

Kincaid, C. A., & Parasnis, R. B. D. B. (1931). A history of the Maratha people (2nd). Oxford University Press.

Wellington, A. W., & Wood, W. (1902), The despatches of Field-Marshall the duke of Wellington during his campaigns in India, Denmark, Portugal, Spain, the low countries, and France, and relating to America, from 1799 to 1815. G. Richards.

S., C. R. G. (2007), The Anglo-maratha campaigns and the contest for India: The struggle for control of the South Asian Military Economy, Cambridge University Press.

Major Thorn, William (1818), Memoir of the War in India, Military Library, Whitehall.

Major Smith, Lewis Ferdinand (1805), A Sketch of the Rise, Progress, and Termination of the Regular Corps, formed and commanded by Europeans, in the Service of the Native Princes of India, London

Article is a fine conclusion to your arduous work, I would like to know the correspondences between Pohlmann, De Boigne, Dupont, Sumroo, maybe we can get some references which prove even more conclusively that this was wellsely engaging with some kind of rear guard.