Prelude to Assaye

A closer look at the Battle of Assaye, 1803, fought between the forces of the Hon'ble East Indian Company led by Sir Arthur Wellesley & the forces of the Maratha Confederacy.

On the 31st of December, Peshwa Bajirao II had signed the document of the Treaty of Bassein, 1802. The treaty was essentially worded as a guarantee of a defensive alliance between the Hon'ble East India Company & His Highness Peshwa Bajirao Raghunathrao Pandit Pradhan Bahadur.

It was this treaty which empowered the Company Bahadur, now an ally of the Peshwa, to restore him to his rightful seat of Poona from where he had been ousted by Jaswantrao Holkar after the Battle of Poona, in October of the same year, when Holkar marched against the forces of the Peshwa & Sardar Daulatrao Scindia, Maharaja of Gwalior.

Our assessment today is not concerned with the overall strategic dimensions & implications of this war, which ultimately the Company won. Nor is it concerned with the performance of the opposing forces throughout the Northern & Deccan theatres.

Instead, today we narrow our analysis to the battle which has come to capture the imaginations of generations of military writers & popular historians as well as the average reader, this being, the Battle of Assaye, fought on the 23rd of September, 1803. The battle was fought on a flat plain surrounded by hilly terrain near the village of Assaye in present day Maharashtra, between the forces of the Company Bahadur under the command of Sir Arthur Wellesley, who had only the previous year in 1802 been promoted to the rank of Major-General, but the man who would one day conquer Napoleon, and the combined forces of Daulat Rao Scindia, the successor to the iconic Mahadji Scindia, the patriarch who took his house to its zenith and the forces of Raghoji II Bhonsle, Raja of Nagpur.

The battle & indeed the war, was an outcome of the sardars of the Maratha power not accepting the terms of the treaty signed by the Peshwa.

Wellesley's Long March :

General Wellesley's march to Assaye began from Seringapatnam in February of 1803, where he gathered his forces & in a flurry of activity prepared his itinerary to reach Poona where he would achieve the first objective of his campaign, that is, the reinstallation of Peshwa Bajirao II.

By the third week of April, 1803, the British force drew closer to Poona, which until now was still held by Holkar's forces, under Amrut Rao. Intelligence suggested that the destruction of Poona was a very real possibility in response to the arriving host & its esteemed companion.

To save Poona from supposed imminent destruction, a force of cavalry was sent dashing forward without infantry or artillery guns. While the protection of Poona intact wasn't of relevance to the war, its value both symbolic & political was undeniable.

Finally, the Peshwa entered his Poona on the 13th of May, 1803, escorted by Wellesley himself.

General Wellesley departed from Poona on the 4th of June, 1803. His next destination was the fortress of Ahmadnagar. The fortress, of medieval fame, had featured in the military history of the Deccan prominently. The acquisition of this fortress allowed Wellesley to contain any perceived offensive threats from the Marathas, while also providing a convenient forward operational base to store supplies in, station in and move troops out of & project strength within the Deccan to protect both the territories of the Nizam and the Peshwa.

Wellesley arrived at Ahmadnagar on the 8th of August, prepared for a siege, while the fort's qiladar refused a letter requesting his surrender on the same day. The Arab garrison within the fort 1,200 strong was supported by a body of light Maratha horse around 3,000 strong stationed between the fort and its pettah. The force was under the command of a Brahman Qiladar, Malhar Kulkarni of Chambhargonda. On the 12th of August the garrison capitulated and marched out.

The Ahmadnagar outpost would prove a memorable one, since the year of 1803, wreaked a famine upon the local population, possibly an outcome of constant pindari movements in the region causing shortages of food supply in the tehsil. Reportedly, more than 5,000 lives had perished due to hunger & an emergency feeding program started by Wellesley helped saved the lives of thousands.

Wellesley's northward march was to obtain a rendezvous with Colonel Stevenson and eventually destroy the forces of Scindia & Raghoji II (Gwalior & Berar). Towards this goal Wellesley had to cross the Godavari towards Aurangabad, yet cross it back to reach its southern bank again, in order to better deter Maratha advances upon allied Hyderabad.

It would seem the Maratha sardars themselves grew tired of the light horse tactics which didn't seem to produce the results they desired. The two began a northward march of their own, to consolidate their forces north of the Ajanta Pass.

On the 21st of September, Wellesley and Stevenson met at Badnapur. They decided on a pincer movement towards the enemy, the latter moving west and the former eastwards, thus, in theory catching the Maratha force between them in order to destroy it completely.

As he moved eastward, Wellesley arrived at Pangree, on the 22nd of September.

From here, Wellesley reached Nalni, 12 miles distance, north of Pangree, on the morning of 23rd, around 11 o'clock.

Intelligence, which was lacking in this entire campaign, had previously suggested that the enemy was to the west of Bhokardan, about 14 miles from Nalni, but the reality was that Bhokardan was the site of the Maratha army's right flank's extreme.

When Wellesley went out for reconnaissance, he noted, that the enemy army seemed to stretch from Bhokardan to Assaye, the enemy right (Wellesley's left) being entirely cavalry and their left being the regular battalion of infantry standing before Assaye.

Seizing the initiative and unwilling to relinquish the gift of surprise bestowed upon him by Fortuna herself, Wellesley chose to march with his force alone against the enemy, abandoning the idea of waiting for Stevenson, to destroy Scindia's Campoos and render the Maratha threat a paper tiger.

The Confrontation :

To understand Wellesley's actions in the afternoon of the 23rd of September, we need to understand how Wellesley saw the Maratha line when he moved northward from Nalni having found the Marathas closer to his position than expected, by 7 miles. He had initially relied on intelligence received from his harkarrahs that the enemy was concentrated around Bhokardan, 12 miles north of Nalni, but what he found was the Maratha line as near as Assaye, only 5 miles northwards.

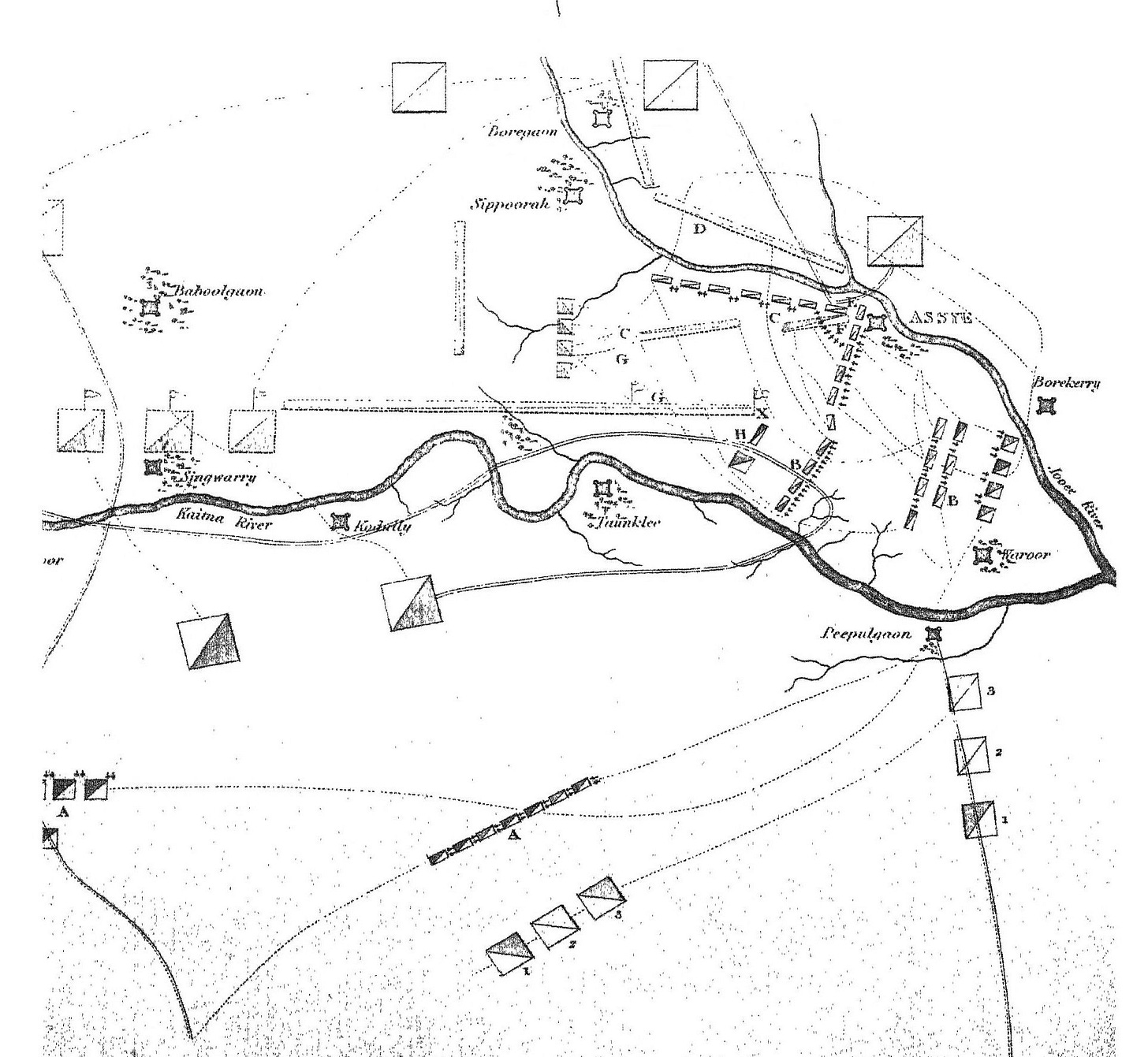

The Maratha force stretched from east to west, Assaye to Bhokardan, roughly 6-8 miles. The Maratha left being Daulat Rao Scindia's regular battalions, trained & equipped in the European fashion and a body of horse to its right, upto Bhokardan.

This force stood on the northern bank of the Kailna or Kaitna river facing south, cushioned between the doab formed by the confluence of Juah & Kailna to their immediate east. The river Juah was thus, north of the Marathas and faced the backs of Scindia's regular infantry. The ground from the confluence of the two rivers to Bhokardan was flat terrain.

Confronted with such a force, arrayed in such a manner, General Wellesley proceeded thusly.

He marched to cross the Kailna at Pipargaon, maneuvering his line at a 90° angle, north to south, from the river. The purpose of this action was to reduce the total number of Scindia's infantry which would be in a position to respond to his advance. This was a typical flanking maneuver, meant to roll up the enemy line by attacking its flanks, thereby exploiting numbers and the surprise element against a narrow frontage of the enemy's line.

The Marathas noticed this movement and responded with artillery fire, while the regular battalions of Scindia performed the difficult tactical maneuver of turning their line at a 90° angle with their right or southern flank anchored on the northern bank of Kaitna, their left or northern flank anchored on the southern bank of the Juah at the hamlet of Assaye, the line ran north-south, facing east, where the Company force was forming up, facing west.

The Marathas also formed a second or fall-back line, this one facing south running east to west, with its eastern-most or left end anchored at Assaye.

The two Maratha lines met at Assaye, which may be understood better as the hinge of a door upon which the two Maratha lines met, running perpendicular to each other at essentially a right angle. The entire layout may be better understood by observing the plan for the battle (see above).

Thus, the two forces were arranged and a chaotic ordeal was to follow.

With this we conclude this part of our analysis. We will pick up the action where we are now departing in a later iteration of this series.

And on that note, my first post ends. I hope you all enjoyed my writing style and found the subject interesting.

Share this post with your friends, if you think this is worth sharing!

References :

Major Thorn, William (1818), Memoir of the War in India, Military Library, Whitehall.

S., C. R. G. (2007), The Anglo-maratha campaigns and the contest for India: The struggle for control of the South Asian Military Economy, Cambridge University Press.

Wellington, A. W., & Wood, W. (1902), The despatches of Field-Marshall the duke of Wellington during his campaigns in India, Denmark, Portugal, Spain, the low countries, and France, and relating to America, from 1799 to 1815. G. Richards.

Kincaid, C. A., & Parasnis, R. B. D. B. (1931). A history of the Maratha people (2nd). Oxford University Press.